Girls were not allowed.

Agricultural-Science was a class for boys who would one day become farmers or ranchers. School-age girls were to take home economics so they could learn to cook and clean. Or so thought educators at Merced High School until they met Mary Callen.

Mary didn’t take a ‘no’ as easily as others and she never backed down from a challenge. Especially after her father fell ill when before she entered kindergarten.

A man just 30 years old, Mary’s father, Daryl, was stricken with a debilitating autoimmune disorder that attacked his joints, leaving his hands and legs nearly useless.

“It is commonly known as Rheumatoid Arthritis today, but to our family, it meant the primary source of income was in jeopardy,” said Mary. “Our father was on the ranch every single day, and then all of the sudden he is in and out of hospitals for two years. When he does return, he is in braces learning to walk and how to use his severely deformed hands.”

Looking to regroup, 7-year-old Mary and her 10-year-old brother, John, would be asked to grow up quickly. The family had a 300 head cow-calf operation in the heart of California’s Central Valley, but with no one to lead the way, the operation was sold to pay the bills. But that did not mean the work was over, the ranches needed to be irrigated and maintained while the tenants’ cattle grazed and were rotated from field to field and the siblings were cheap labor. It is then that she learned that life would not always come easy.

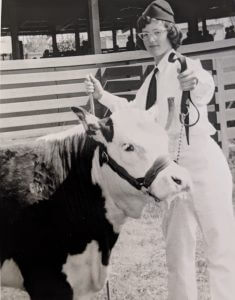

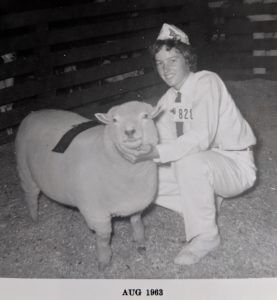

At school she would be faced with discrimination that was deemed acceptable for the time. In the 1950s and 60s, Future Farmers of America did not allow girls into their program, but that does not mean she wasn’t expected to carry a project and complete records like everyone else.

Despite pushing her way into the Ag-Science course and being a Merced County’s 4-H All Star, she was told to stand outside when the FFA portion began. Many days, temperatures were in the 30s and 40s. You’d think that would have diverted Mary into a different career. But it didn’t.

She showed up day after day and earned the respect of her classmates because of her work ethic. While the boys in her class were not inclined to challenge the teacher, many expressed to her privately their support over the unfair treatment.

“The support they gave was greatly appreciated as my father passed away my senior year in high school.”

Mary would see her best friends receive hands-on teaching from their dads while horseback on the range or working at the chute and it is during those days the pain was the deepest.

After graduation, Mary’s mother sent her only daughter off to California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. Both knew it would be Mary’s own work and scholarships that would make it happen.

After graduation, Mary’s mother sent her only daughter off to California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. Both knew it would be Mary’s own work and scholarships that would make it happen.

“I remember the goodbye as Mom was about to leave the dorm. She pulled $7.50 from her purse, which wasn’t much then either, and she said that she wished it was more. I felt really guilty about taking that money but I knew it would hurt her more if I refused.”

While class sizes were larger in college, the ratio still didn’t change much. Mary was the only female in her classes and in four years wound up becoming only the third woman in school history to graduate with a farm management agricultural-economics degree.

“At least I didn’t have to stand outside,” Mary said with a laugh.

That degree would become vital in 1977 when she was tasked as the first employee of the Westside Water District. Taking over her grandfather’s rangeland and dryland farm ground that was slated for water service from this new district outside of Williams made her the perfect choice for the “Secretary” position. Though she was much more than someone who took notes and calls.

Mary managed loans and funding for construction of Westside’s water distribution and drainage systems from the Tehama-Colusa Canal. Soon enough she would become General Manager and even the board director – positions more accurately depicting her duties.

Following construction, the challenge on the table was how to balance the Bureau of Reclamation’s Management and Conservation Plan with the needs and practices of the farms in the district.

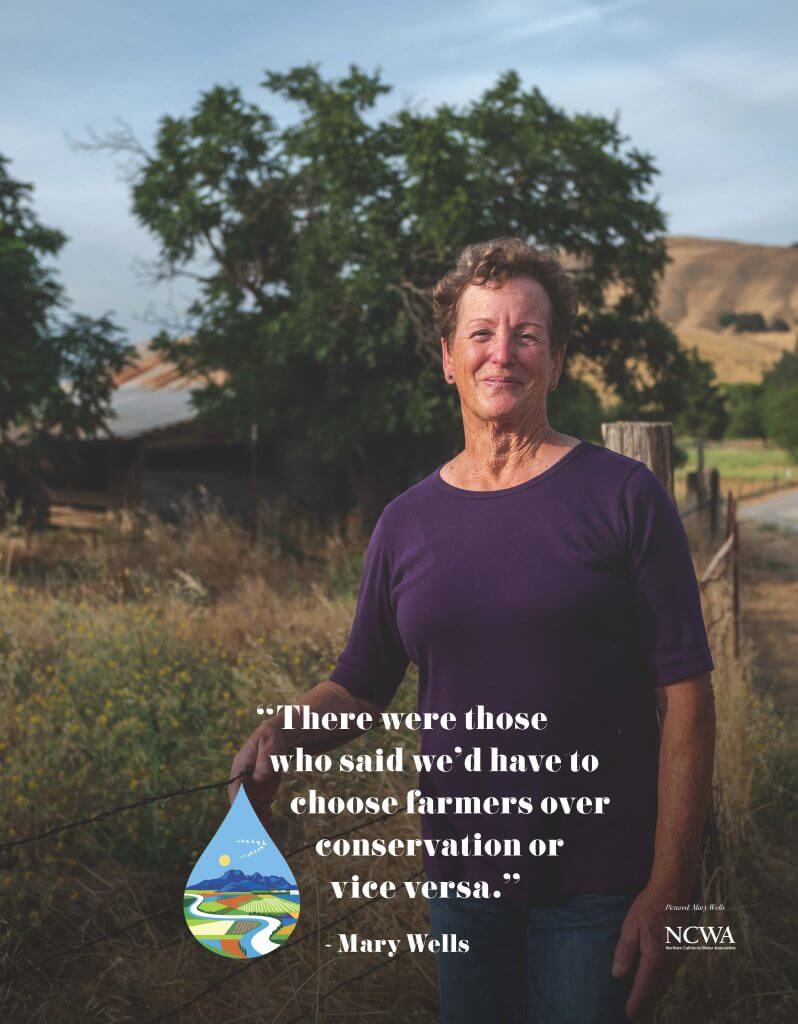

“There were those who said we’d have to choose farmers over conservation or vice versa.”

“There were those who said we’d have to choose farmers over conservation or vice versa.”

Like many of the other choices Mary was presented with in her life, she didn’t take that offer. She chose both.

Mary played a role in creation of the Reclamation Reform Act of 1982, the Federal Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA) of 1992 and the Red Bluff Diversion Dam fish passage efforts. Add that to the Bureau of Reclamation service and settlement contract renewals and agricultural irrigation needs and environmental requirements started to find a real balance with Mary in the middle of it all.

“We had the opportunity to showcase that we could use our water to grow rice and benefit wildlife year round. We learned the best way forward to preserve our water rights was to grow rice efficiently and then think of innovative ways to also use that water to benefit habitat and better the environment shared by the native fish and waterfowl species.”

For Mary, it was more than just words. She advocated that the Maxwell Irrigation District participate in an innovative fish food program during the summer that directs water through a wetland and tidal slough corridor of the Sacramento River system and into the Delta.

Why? To help feed endangered fish downstream.

Results were instantly positive. It showed that the nutrient-rich “pulse flow” successfully generated a phytoplankton boom and enhanced zooplankton growth which greatly aided the Delta smelt and their egg production.

“In conjunction with our fellow water users, we worked with various Sacramento Valley agencies, the California Department of Water Resources and the Department of Fish and Wildlife to facilitate and minimize the impact of reduced water service for a mid-summer week in order to see this science-based concept through.”

It is one example of many where Mary Wells, as she is better known, took the more difficult path in hopes of finding a positive and impactful result for the greater good.

Because of her tenacity, Mary is one of the most respected water managers and policy leaders in Northern California. She was a founding director of Northern California Water Association and served as its chairperson for six years. Her fighting spirit has been contagious and helped give many other women the courage to follow their own paths into agriculture.

“I look back now, and I think how my father’s illness and death prepared me for the rest of my life. I saw him keep fighting and have a positive outlook during that difficult time. It helped shape the attitude I had with each challenge I faced and continue to face.”

Mary still owns land in Williams and Maxwell which is now operated by her children and grandchildren. And these days, the no’s are a little less frequent, because as most understand by now, Mary is likely going to find a way to do it anyway.

Listen to the podcast here.

This story would make a great movie.