By Kevin O’Brien

I’m not a farmer. I’m not a landowner in RD 108. I’m certainly not a member of the RD 108 Board of Trustees. But I have had a unique vantage point, over the past quarter century, to observe RD 108 in my role as District legal counsel. I’ve been closely involved in some very important—and at times very difficult—decisions. I’ve seen—up close and personal—how RD 108 goes about its business. And when I talk about RD 108 I don’t just mean the Board of Trustees. I mean the whole enchilada—the landowners, the farmers, the management, the staff, the consultants and, yes, the Board of Trustees.

I’ve also worked with a number of other districts around the state. I have a pretty good basis for understanding how RD 108 is unique and I’d like to discuss that with you this morning.

When I think about the predominant ethic of the Sacramento Valley the word that comes to mind is “stewardship.” In this context, “stewardship” means the acceptance of responsibility to safeguard resources for the benefit of future generations. Based on my personal experience, RD 108 is the embodiment of the stewardship ethic that exists in the Sacramento Valley. It’s not the only place where that ethic exists but it is a powerful example of how the core value of stewardship can be brought to bear to solve problems.

The Sacramento Valley is a unique place. Its uniqueness stems, in part, from its physical resources—the fertile land, the abundant water, the wetlands, the wildlife, the birds and the fish—all knitted together in one remarkable ecosystem.

But the Sacramento Valley is more than just the sum of its physical attributes. It’s also a product of human inputs. The culture of the Valley reflects the ethic of the people and families who have lived and worked here—in many cases for several generations.

The stewardship ethic exists in the Sacramento Valley not just because it was passed down from individual to individual or family to family but also because it lives within institutions—community organizations, private businesses and, yes, public entities. This morning we celebrate the 150th anniversary of one such public entity, Reclamation District No. 108. In these brief remarks I’ll provide some examples—based on my own personal observations and experiences over the past quarter century— of the RD 108 stewardship ethic in action.

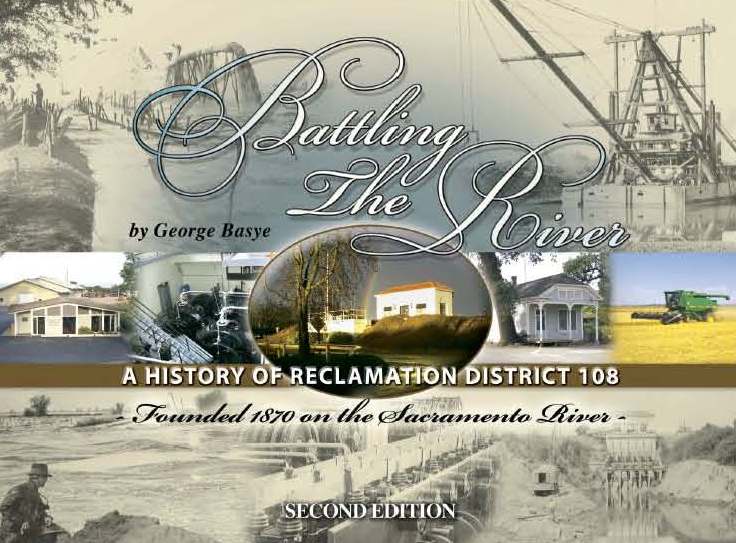

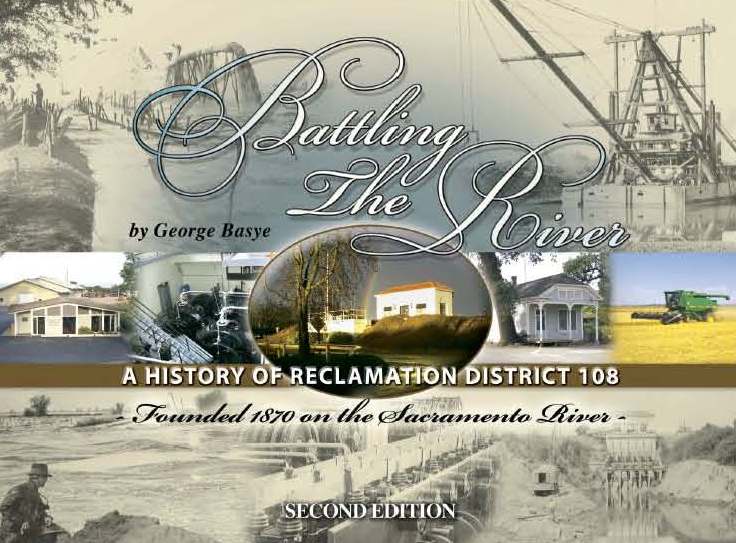

I do not claim to be an expert on the 150-year history of RD 108. The best source on that topic, of course, is the wonderful book written by my mentor and predecessor as District legal counsel, the late George Basye. That book is entitled Battling the River and it traces the District’s history from its formation in 1870 through approximately 2010.

I do not claim to be an expert on the 150-year history of RD 108. The best source on that topic, of course, is the wonderful book written by my mentor and predecessor as District legal counsel, the late George Basye. That book is entitled Battling the River and it traces the District’s history from its formation in 1870 through approximately 2010.

For those of you who haven’t had an opportunity to read George’s book, let me take a few moments to describe a few highlights from the District’s history.

The first thing to understand is that the lands comprising RD 108 were originally swamp land. The term “Reclamation District” comes from the Arkansas Act passed by Congress in 1850, which provided for “swamp and overflowed lands” to be granted to the States, such lands to be “reclaimed’ for productive use. In 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War, the California Legislature provided for the formation of Reclamation Districts.

In 1870, the Board of Supervisors of Yolo County entered an order forming the district. A few month later, the State Lands Office assigned the number 108 to the new district. It was initially referred to by the State Land Office as “Swamp Land District No. 108” but the term “Swamp Land” was later changed to “Reclamation.” From my perspective that was a very good move.

I’m considering ordering a supply of “Swamp Land District No. 108” baseball caps, just to commemorate this early history. We can have a competition on how best to depict the swamp in its full artistic splendor.

Immediately following its formation the District began construction of a levee on the west side of the Sacramento River and, later, the construction of a drainage facility along the west side of the District and an additional levee, commonly known as the “back levee.”

On the water supply side, the District applied for and obtained appropriative water rights from the State of California. It constructed an extensive irrigation system.

All of these activities involved human commitment and sacrifice. The costs borne by the RD 108 landowners during this early period were staggering. Hard times ensued and the Great Depression loomed. As late as 1935, the Pacific Gas and Electric Company refused to accept District warrants for the standby charges for power at the Rough and Ready pumping plant. But with sound management the District got its financial house in order and ultimately flourished.

Following the completion of Shasta Dam in 1945, the District, along with other water right holders on the Sacramento River, entered into lengthy negotiations with the Bureau of Reclamation, culminating in the execution of the original Sacramento River Water Right Settlement Contracts in 1964. These contracts were renewed in 2005.

Reviewing this history one quickly realizes that the people who settled this land were tough. They were resilient. They were mavericks. And stewards.

In George’s book, the very last chapter is entitled “Accommodating the Environment.” It describes the early stages of what would become a new set of challenges for the District—challenges that involve the balancing of the needs for a reliable irrigation water supply with the needs of the environment. This is where my representation of the District started—in the early 1990s—and where Fritz Durst began his tenure on the Board of Trustees.

RD 108 engaged on environmental protection with the same energy, creativity and focus that it brought to its earlier challenges. Fritz and I were on some of the early trips to Washington, D.C. to meet with then-Representative Vic Fazio, the Bureau of Reclamation and other federal agencies. The subject was funding for fish screens. In 1992, a federal district judge in Sacramento had issued an order enjoining the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District “from pumping water from the Sacramento River at its Hamilton City facility during the winter-run chinook salmon’s peak downstream migration season of July 15 through November 30 of each year.” The world was changing and we knew it.

Emery Poundstone was the president of the Board of Trustees during this period. I recall vividly attending meetings in Washington with Emery, Fritz, Luther Hintz and Gaye Lopez. I learned a lot watching Emery interact with Congressman Fazio and the federal agencies. I suspect Fritz would say the same. Emery was strong yet civil, congenial yet focused.

The District was ultimately successful in obtaining the federal and state funding for its fish screen projects and in building and operating the screens. The largest is right across the road at Wilkins Slough.

Other challenges followed. Litigation was commenced challenging Reclamation’s execution, in 2005, of the renewed Sacramento River Settlement Contracts. Some issues from that litigation are still being litigated.

The State of California pursued requirements for additional outflow to the Bay-Delta Estuary to support fish populations. During the recent drought the need to preserve cold water in Lake Shasta to reduce temperature-dependent mortality in salmon has become a central issue in regulatory processes and litigation.

These are not easy issues. But as has been the case throughout its history RD 108 has risen to the challenge. It has been guided by the ethic of stewardship. It has provided important leadership in advancing the Voluntary Agreements process as a mechanism for helping our fish populations recover. It has built and operated projects to protect fish in the Sacramento River watershed. It has played a pivotal role in the Northern California Water Association and organizing the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors who have become a well-coordinated and effective voice in the various regulatory processes. It has been an integral participant in the effort to build Sites Reservoir.

It has been said that leadership is the capacity to translate vision into reality. At RD 108, during my tenure, the vision has always been clear: a vision rooted in the ethic of stewardship to move away from the old paradigms—farmers versus fish, north versus south. And right now, as we speak, this vision is being translated into reality. That’s the product of a lot of work and vision by a lot of people and organizations, not just RD 108, but RD 108 has been at the center of the effort.

I have no doubt that it will succeed.

on June 29, 2022.