How Meghan Hertel’s failed farming attempt was a boon for wild birds in California

How Meghan Hertel’s failed farming attempt was a boon for wild birds in California

There wasn’t an older brother or sister. Single mother worked full time, and in an age when this was normal, the outdoors became her babysitter.

Few of her friends lived in the same Pinehurst, North Carolina neighborhood, so Meghan was left with the trees, rocks and her imagination to pass the time. She didn’t know it then, but those days under the southern sun would play a vital role in shaping her adult life.

Not sure if it was the Fisher-Price toy barn set that glamorized the trade, but Meghan had a calling.

As a 21-year-old, the Carolina girl would fall in love with one of America’s first professions, farming.

Days after graduating college, Meghan would find herself outside of Atlanta taping tomato vines, laying irrigation lines and packing up blueberries to sell at the local farmer’s market. But something was amiss.

“Farming is extremely hard work; it is nothing like what I imagined or dreamt it to be as a little girl,” said Hertel.

“After putting the farmer’s tractor out of commission. The writing was in the soil. It was time for me to move on.”

Landing in Sacramento, Meghan believed she could blend her understanding of farming with her love for nature.

“You don’t have to do one or the other. We need to figure how to balance both the production of our food with environmental stewardship. How to help the environment in urban and rural areas.”

“You don’t have to do one or the other. We need to figure how to balance both the production of our food with environmental stewardship. How to help the environment in urban and rural areas.”

Audubon California provided just the opportunity.

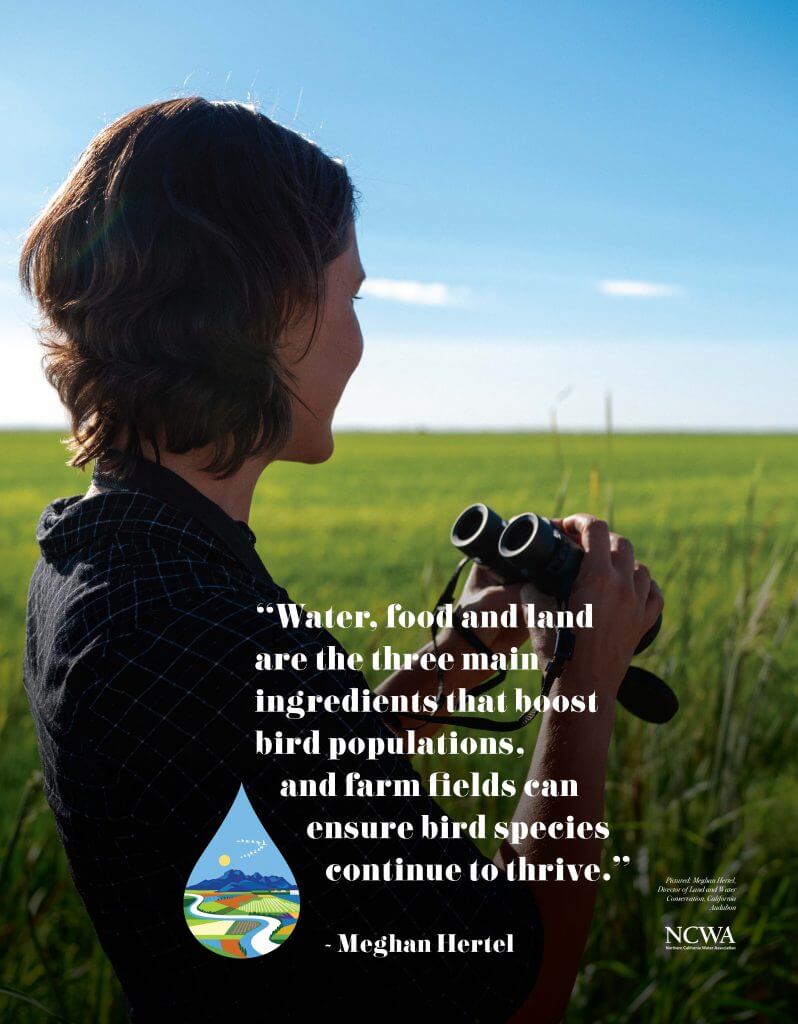

In her role as Director of Land and Water Conservation, Hertel discovered birds offer a key to understanding the overall health of a particular environment.

“Birds, like us, need clean air, clean water, and they are often the first to respond when conditions take a turn for the worse.

They are the canaries in the coal mine in nature. Where birds thrive, people thrive.”

Hertel worked with farmers throughout the Sacramento Valley to demonstrate how birds and insects on farmlands can result in a positive impact on crop production.

“Farmers need specific water allocations for fields, or the fields may turn fallow. When they do, people and birds are impacted,” Hertel adds. “Water, food and land are the three main ingredients that boost bird populations, and farm fields can ensure bird species continue to thrive.”

Today, several hundred thousand acres of farm fields in Northern California are not only providing food for people, but are vital for the survival of ducks, geese and shorebirds along the Pacific Flyway year-round.

The experience with Audubon led Meghan to a new post with the California Natural Resources Agency.

It is here where she is not only helping farmers and birds, but on the same floodplains, the work has expanded to helping direct actions that will provide fish habitat, recharge groundwater supplies and maintain flood protection for the valley.

As the Deputy Secretary for Biodiversity and Habitat, she is focused in on reactivating the Sacramento River Basin floodplains while also working statewide to help create and foster the development of large-scale habitat projects.

So, in what seems to be twist of fate or a maybe a bit of irony, what was once the great outdoors that watched over her, it is now Meghan Hertel that looks after the great outdoors.

Listen to the podcast here.

Sites Reservoir would capture and store stormwater flows from the Sacramento River – after all other water rights and regulatory requirements are met – for release in dry and critical years for environmental use and for California communities, farms, and businesses when it is so desperately needed.