Ralph Gorrill was one of those astute types, he could see a problem and know the answer would be found at the tip of his drafting pencil.

A builder seemingly at birth, it was only fitting that he would be nose deep into those back-breaking, 50-pound text books at the University of California, Berkeley. It was underneath the famed Campanile Clock Tower that Ralph found himself confident he would soon be an engineer just like his brothers.

With a degree in hand, Gorrill landed 150 miles north of the East Bay hoping to follow his brothers in finding work in the rural Sacramento

Valley.

Before the modern-day Highway 99 would be the main thoroughfare, in 1917, only a variety of country roads connected the rural towns of Northern California.

Ralph landed a job creating a better route for ranchers and farmers delivering cattle and wheat.

With his drafting pencil in hand, Ralph drew up a solution for the main road, known as the Midway, that would cut hours off of delivery times.

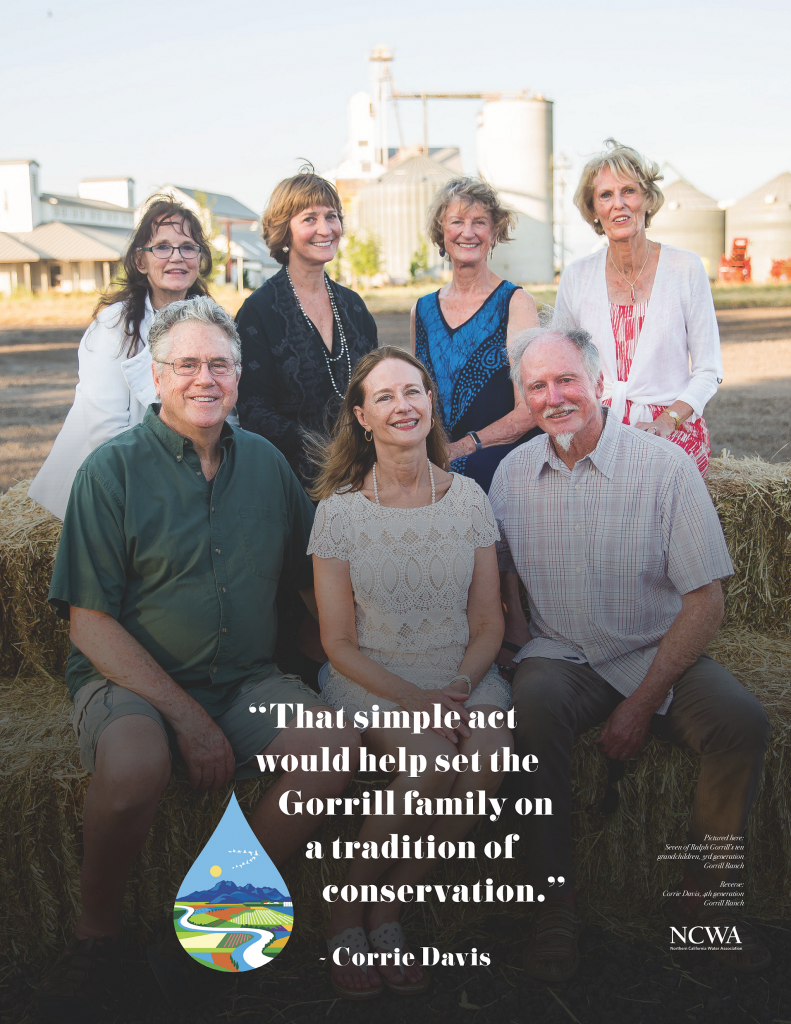

“Little did he know that this two-lane strip of roadway would wind up setting him on an entirely new path,” said Corrie Davis, a fourth-

generation family member who serves as the managing partner and chairman at Gorrill Ranch.

The Leland Stanford Trustees were looking to sell their 17,000-acre Durham Ranch (of which Ralph bought a portion) along that very same strip of concrete Gorrill had helped create. The engineer had the inside track on the gossip as his brother-in-law was also the ranch manager on LST farm.

“What has always fascinated the family, is that our great-grandfather wasn’t a farmer, yet he was confident that he could make use of this farm that hugged Butte Creek. He saw real potential there,” said Davis.

A thick adobe clay spanned the property, which meant this land was prime for something other than cattle. The unique soil combination was a perfect recipe for rice. Gorrill Ranch is now known internationally for their quality premium rice.

A thick adobe clay spanned the property, which meant this land was prime for something other than cattle. The unique soil combination was a perfect recipe for rice. Gorrill Ranch is now known internationally for their quality premium rice.In a state that is no stranger to prolonged droughts, Gorrill wanted to make sure he used whatever water he had, as efficiently as he could.

“He truly became fixated on constructing the best irrigation system in the Sacramento Valley.”

Using gravity and leveling the clay at precise angles, Ralph crafted a sprawling web of water that reached every bend, edge, and corner of his fields.

“He never knew the meaning of doing something halfway. He built his labyrinth of pipes so well that our family still uses that same irrigation system to this day.”

Whether he knew it or not that simple act would help set the Gorrill family on a tradition of conservation.

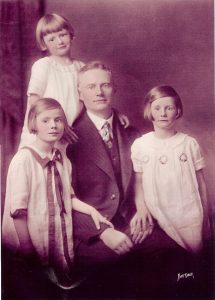

When he passed away in 1964, Ralph’s daughters Sally, Jane and Anne took over the farm.

When he passed away in 1964, Ralph’s daughters Sally, Jane and Anne took over the farm.

Throughout their reign on the family ranch, the sisters turned their attention up to the sky and down below the river surface. First, helping to create a comfortable place to rest for birds along the Pacific Flyway with their rice fields.

There are now 40 acres of land set aside as an environmental preserve. And second, to help their underwater friends in Butte Creek.

Their timing couldn’t have been better. By the late 1990s, Chinook salmon were disappearing at an alarming rate.

“We owe much of our success to Butte Creek,” added Davis. “And our family knew it was time to prevent the creek’s main inhabitants from disappearing.”

Joining other neighbors, many whom operate along the same Midway trail that Ralph once helped design, the Gorrills and this coalition of farmers, environmental groups, and other agencies dove head first into a massive restoration project known as the Butte Creek Fish Restoration Project.

The group retrofitted dams and screens to protect fish from entering irrigation systems. Then, the group built fish ladders to help the fish swim upstream throughout the summer and winter months.

Today, up to 10,000 fish make their way through each spring spawning season.