Twenty years ago, implementation of the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA) began, bringing about a new era of fish passage improvement. The legislation established two programs, the Anadromous Fish Restoration Program (AFRP) and the Anadromous Fish Screen Program (AFSP) which authorized federal funding for fish passage and fish screen projects.

The AFSP, in particular, created the ideal opportunity for federal, state and local entities to come together in a voluntary manner to enhance fish passage. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Sacramento Valley. Over the past two decades, more than one billion dollars ($1,000,000,000) has been spent on fish passage improvements in the Sacramento Valley. The majority of that funding has been spent on the construction of state-of-the-art fish screens. The investment of these federal, state and local funds in the fish screen projects has helped to enhance fish passage for endangered or threatened species of salmon and steelhead in the Sacramento River and its tributaries. Salmon and steelhead are anadromous fish. They are born in fresh water, spend most of their life at sea, before returning to fresh water to spawn. During this life cycle, they pass by the diversions in the Sacramento River as they out-migrate to the ocean and also when they return to spawn. The installation of fish screens on these diversions allows the fish to avoid being taken or stressed.

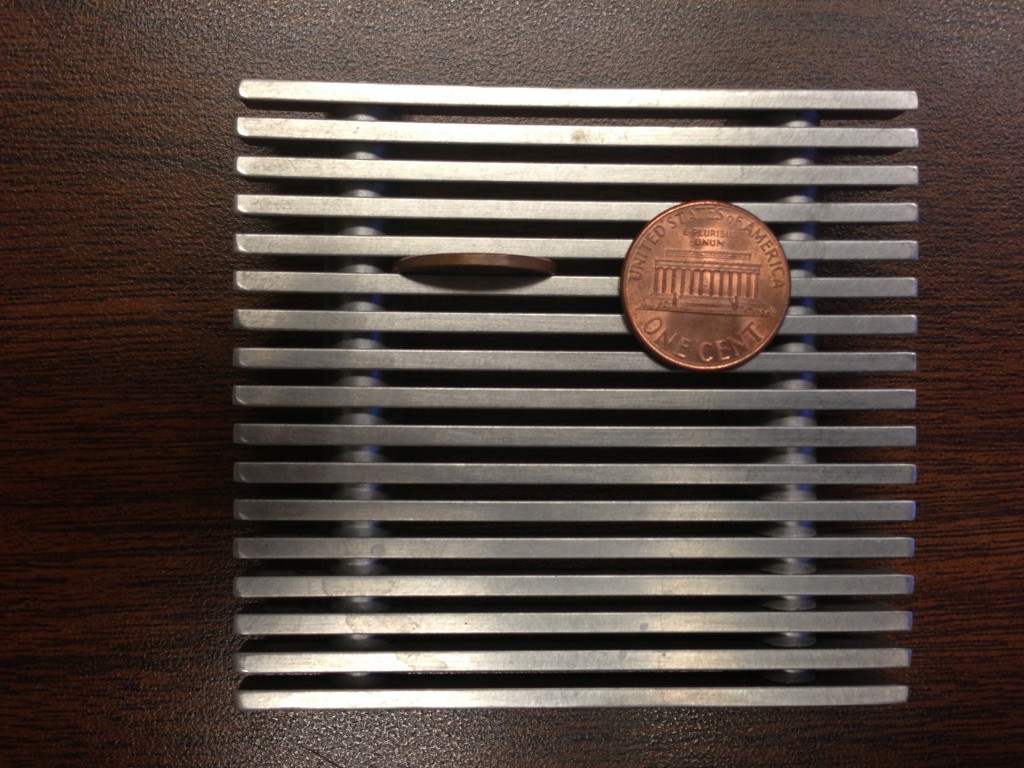

The engineering behind fish screens is fairly straight forward. The fish screen creates a barrier between the fish in the river and the pumps used to divert water. The larger the pumps, the larger the fish screen. This ensures that water moving through the screen does so no faster than one foot every three seconds, thereby creating no chance that even the smallest juvenile salmon would be impinged on the screen or even have its equilibrium disturbed if it is swimming by a diversion that is pumping at maximum capacity. The screen is also constructed with gaps small enough (not much larger than the thickness of a penny) that not even the egg of an endangered or threatened species of fish could make it through a screen. In order to achieve this, screens need to cover a large surface area. The recently constructed Natomas Mutual Water Company screen is 158 feet long and the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District fish screen is 1,100 feet long, or almost a quarter mile in length.

Today, all of the high priority fish screen projects on the Sacramento River have been screened or are in the process of being screened. At this point, over 80 percent of the agricultural water diverted from the Sacramento River goes through state-of-the-art fish screens. This has essentially created a migratory corridor which has enhanced the likelihood of successful passage for these fish in the Sacramento River.

While anadromous fish must survive long migrations to and from the sea as well as several years in the ocean, the screens constructed by local, state and federal partners during the past two decades, with help from the Anadromous Fish Screen Program, have made that journey easier and more successful.